Nemo Studios: Potrait of a recording studio

By the late 1960s, studio recording equipment had reached a new level of maturity. The latest technological developments meant that state-of the-art multitrack tape recorders, mixing desks, noise-reduction equipment and a multitude of audio outboard equipment transformed the professional recording studio. This ultimately lead to an increase in the audio sound quality of the recordings and opened up a host of new possibilities for sound producers, who were then able to obtain production techniques previously unimaginable.

However, with this vast array of equipment, it also meant that, proportionally, the recording of compositions took longer to complete, both at the production and mixing stages. Much of the time was spent either editing or at the mixing desk rather than recording the music.

The advantages of owning a private recording studio were apparent. It enabled total creative freedom for musicians to work on a number of simultaneous projects more efficiently, and it gave them time to perform musical experiments before albums were submitted to the record company. Another advantage was that it avoided booking commercial studio time, which removed the burden of moving heavy instruments from one studio to another.

Since the operational costs alone would have been prohibitive for most musicians’ budgets during the mid-1970s, only the most capable or entrepreneur-minded musicians ventured into establishing their own private recording studios. Vangelis’ own music laboratory, Nemo Studios, was such a studio, and it was established, in London, in 1975. For a time period spanning 13 years, Nemo Studios witnessed the launch of Vangelis’ music career on the international scene, and it was the birthplace of several albums and film scores that earned Vangelis critical praise and popular acclaim.

Nemo Studios: 1975-1977

Before Vangelis obtained the premises at Hampden Gurney Street, the area was previously used by a commercial photographic studio, which utilised the location to build large sets for advertising films and fashion catalogues. However, Vangelis was unable to use the area straight away, because it needed a number of structural changes, so construction workers were brought in to turn the large photographic studio into an area suitable for a recording studio.

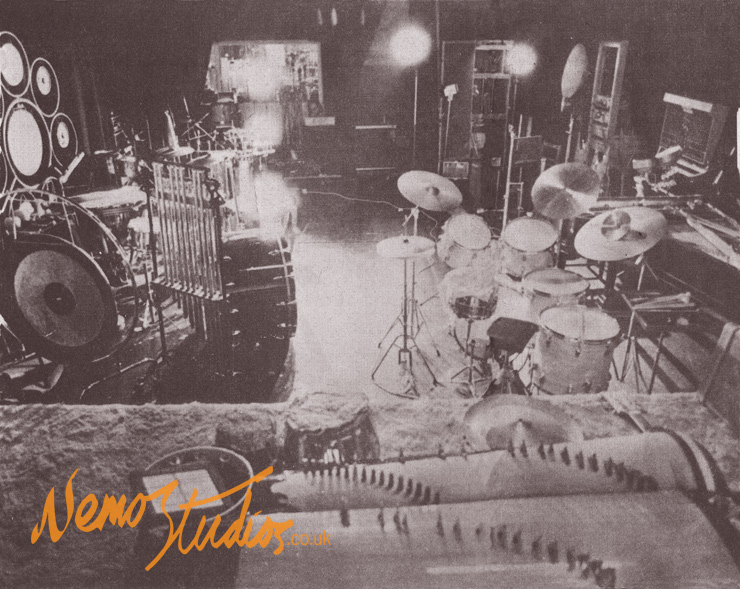

In keeping with conventional studio practices, the premises were divided into two areas. One section, which used to be a large kitchen combined with a darkroom, was made into the studio’s control room, and was designated to housing the recording equipment and mixing desk. The other, larger, section was transformed into the live room, and it contained a removable wooden stage and a cyclorama. Both these items were retained from the photographic studio in case they could be used when performing live music.

The live room’ windows were blocked up and the walls and ceilings were painted black. Curtains were hung on all walls. Initially, there were issues with standing waves in the studio. This was not too detrimental to the sound environment inside the studio, but audio rumble affected the neighbouring buildings, which was a particular problem when working late hours at night. The studio’s roof was thin and acted like a huge wooden loudspeaker, which resonated at low bass frequencies. The problem was fixed by adding mass to the ceiling and concrete paving slabs on the roof.

The wooden stage in the live room was surrounded by a three-sided cyclorama. The stage was useful for recording delicate instruments, such as the Asian harp and the guitar, especially when capturing finger movements was integral to the instrument’s sound. Other musical experiments took advantage of the natural acoustics of the building. For example, the well of the stairway leading to the studio’s entrance provided a natural echo for percussion work.

The control room and live room were divided by a partial brick wall, which incorporated a fireplace. A removable glass window was added to completely seal off the access between the two rooms. This arrangement prevented sound leakage when monitoring the audio in the control room. A talkback function was added to allow the performer and the studio engineer to communicate through the glass window. The window was removable, and, if needed, it could be taken out to reopen the spaces between the two rooms.

At the end of the control room stood a sloping wall. The sloping wall was detrimental for recording live work, as it created acoustic problems. Initially, soundproof consultants advised Vangelis to brick up the wall, to make it straight, but that idea was dismissed in favour of retaining aesthetics and keeping the desperately needed space in the control room. In subsequent years, the wall was used to display Vangelis’ disc awards, until the entire wall surface was virtually covered up.

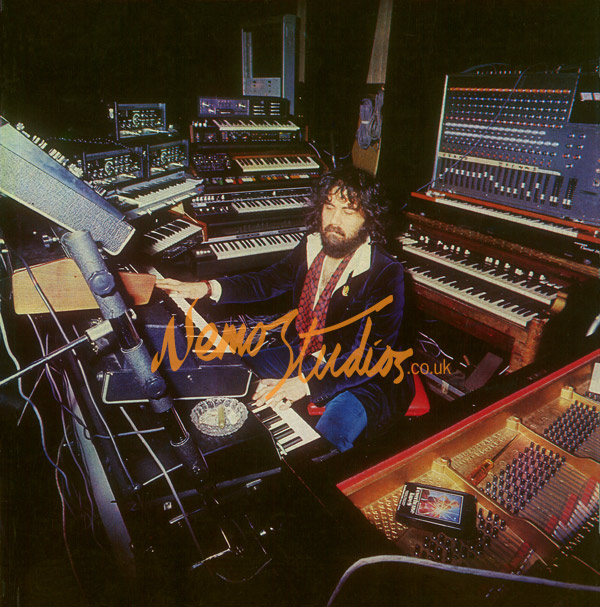

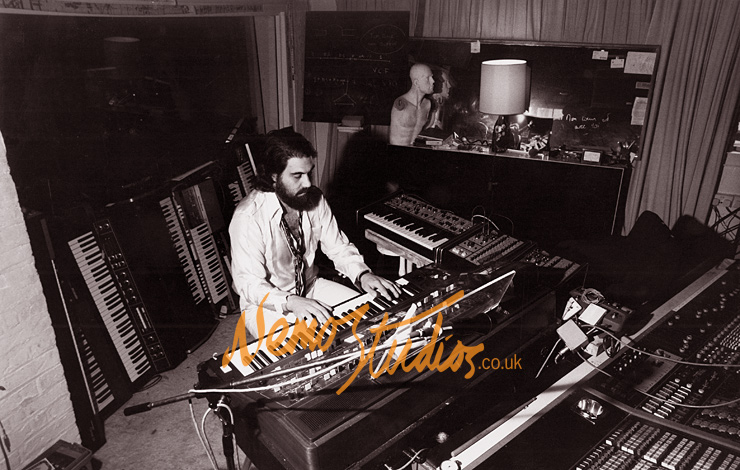

Vangelis at Nemo’s live room. For the first couple of years the sound palettes at Nemo Studios featured the grand piano, percussion, woodwind, acoustic percussion, preset synthesisers, and various types of electric keyboards. Keyboards shown:

Roland SH-3A

ARP Pro Soloist

Korg Polyphonic Ensemble 1000

Fender Rhodes 88 Electric Piano

Farfisa Syntorchestra Organ

Korg MiniKorg 700

Roland SH-2000

Elka Rhapsody 610 String Machine

Hohner Clavinet D6

Hammond B3 Organ

Augmenting the electric keyboards were a range of electronic devices, which always played a key part in achieving Vangelis’ sound textures. These included reverb, echo and distortion units. They aided Vangelis to shape sounds from his electric keyboards and other instruments. The sound modules were typically placed next to Vangelis’ keyboards for easy access. A number of them would be chained one after the other for creating unearthly patches. The devices used at this stage were the Roland RE-201 Space Echo and several Binson Echorecs. These were later joined by the AKG BX-25 and a ‘Master Room’ spring reverb.

Nemo’s first recording equipment

The first recording equipment at Nemo Studios included a customised 24-channel mixing desk, made by Automated Process, Inc., and a customised tape recorder based on the Scully 280 model that allowed recording in 2, 4, 8, 16 and 24 tracks. The customised Scully had three tape transports, but it was usually configured so that simultaneous recordings of 16 multitrack and two 2-track tapes were allowed, each using a dedicated tape transport.

Both the API mixing desk and Scully tape machine were purchased second-hand from ‘Command Studios’, a well-known commercial recording facility based near London’s Green Park, where Vangelis had worked before moving to Nemo Studios.

For audio monitoring in the control room, four Tannoy HPD (high-performance dual-line) monitors, which were built by Lockwood Monitors, were put into professional cabinets. The control room was covered with thick carpets and heavy curtains, which absorbed a lot of the volume. Typically, the monitors would be set to moderately loud, but not at a deafening volume, and not for long periods of time. This was so they did not overdrive the monitors. During the final mixing, another audio check could be patched onto small speakers, which were placed on the mixing desk. This step helped to verify the final mix on the smaller speakers.

Nemo’s choice for noise reduction

The dynamic nature of Vangelis’ compositions often stretched the limits of the recording equipment, and during the first year there was an ongoing technical problem with the somewhat noisy Scully multitrack tape machine. An example of this is when Vangelis’ music goes from a very quiet piano solo to a sudden full-synthesised orchestra, or vice versa. The dynamics posed challenging problems with the Scully tape recorder, making it difficult to bring out the solo parts in the mix. So when the crescendo died out, it left behind 16 tracks of hiss.

To remedy this problem, it was found that the dbx Type-I noise-reduction unit was helpful. So a 16-channel dbx Model 216 was purchased and applied to the 16-track recordings, to increase the dynamic fidelity and reduce hiss. The dbx was a far less popular noise-reduction system among professional studios compared with Dolby, but Vangelis liked the subtle characteristic sounds it gave to his recordings. The dbx also tidied up the sound, as well as offering a wider dynamic compression than Dolby. dbx noise reduction was first used on multitrack tapes for ‘Albedo 0.39’, and it was used for almost all of Vangelis’ subsequent works. On the other hand, Dolby A-Type noise reduction was used for encoding the final master 2-track recordings on the Scully.

|

|

|

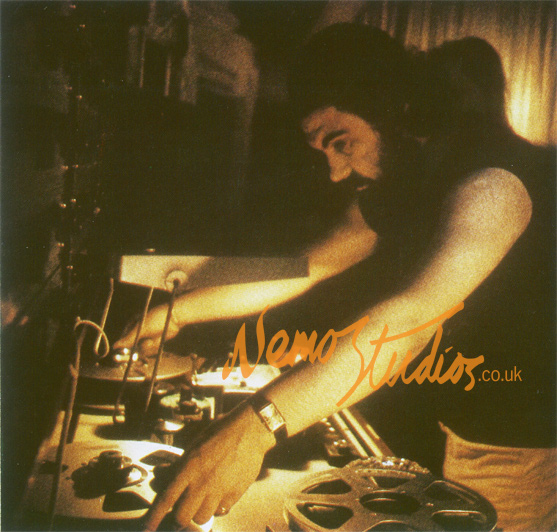

Vangelis operating the Scully tape machine with 2-inch multitrack tape. Vangelis used a modified Scully that functioned as both a multitrack tape and final master tape machine. The Scully tape machine was used for recording all his solo albums for RCA.

Besides composing music and putting composition to tape, the post-production aspect, with analogue multitracked tape recordings, was labour-intensive and required an appreciable amount of time to achieve certain results. For example, inventive sound textures were developed by occasional overdubbing or layering, which helped to enhance the sound after the composition was laid onto tape.

If Vangelis felt a certain part of the melody needed a symphonic sound, then it was overdubbed. The aim was to multiply the sound possibilities of the instrument with a clever combination of sound-processing effects or overdubbing multiple layers.

During the process of overdubbing sound sources some of the early electric keyboards were of low audio fidelity. This problem occurred when an instrument was overdubbed a dozen times or more. The combined sound would begin to deteriorate to reveal undesirable high frequency artefacts. To limit such artefacts frequency templates were employed on a 27-band graphic equaliser for masking them.

Dubbing multiple layers achieved a similar effect to an ensemble of string players in an orchestra. There where slight differences, as, in an orchestra, each individual player adds to the richness and fullness of an orchestral sound. This was achieved by overdubbing the same melody several times and adding subtle differences to each performance, Vangelis also created a similar effect on his early keyboards.

One of the most recognisable instruments in Vangelis’ music is the Yamaha CS-80 analogue synthesiser. Vangelis first spotted the CS-80 at a music fair show in London in 1977, where upon he decided to try one out. It was the first polyphonic synthesiser with true performance features, such as after-touch and velocity-sensitive capabilities, and both of these features appealed to Vangelis. At this time the CS-80 had not been officially introduced to the UK market, and there was already a six month waiting list for the instrument. Vangelis managed to get one on loan for a couple of weeks before deciding whether he wanted to buy one or not. He used the borrowed CS-80 to record the album ‘Spiral’ and the instrument was featured on the majority of his compositions onwards.

To avoid the six month waiting list, Vangelis’ first CS-80 synthesiser was purchased from Japan and train-ferried all the way across Russia to the UK. When the CS-80 first arrived in London it needed the usual internal circuit alterations, so that its voltage was compatible with the UK’s.

Synthesisers: 1975-1977

ARP Pro Soloist

ARP Solina String Ensemble

Dubrecq Stylophone 350S

Crumar Compac Piano

EKO Stradivarius

Elka Rhapsody 610 String Machine

Elka Tornado IV Reed organ

Farfisa Syntorchestra Organ

Fender Rhodes 88 Electric Piano

Hammond B3 Organ

Hohner Clavinet D6

Korg MaxiKorg 800DV

Korg MiniKorg 700

Korg Polyphonic Ensemble

Moog Satellite

Roland SH-1000

Roland SH-2000

Roland SH-3A

Roland System 100

Selmer Clavioline

Yamaha CS-80

Continues on next page, Nemo Studios: 1978-1982

Nemo Studios: 1978-1982

By the mid 70’s a new generation of analogue synthesisers emerged. They featured some compelling developments which offered new possibilities in the realms of performing live expressive music. These synthesisers incorporated polyphonic capabilities which allowed the musician to play chords, or bass lines along the melody lines. In 1977 Vangelis was introduced to the Yamaha CS-80 analogue synthesiser. It was the first polyphonic synthesiser with true performance features, such as after-touch and velocity-sensitive capabilities, and both of these features appealed to Vangelis. He used the CS-80 to record the album ‘Spiral’ and the instrument was featured on the majority of his compositions onwards.

After the introduction of the CS-80 analogue synthesisers such as the ARP Odyssey, ARP Sequencer, Roland System 100, and Oberheim 4-Voice, the new instruments quickly began to replace electric keyboards as the main choice of symphonic instrumentation. Unlike the electric keyboards, the new synthesisers suffered less intrinsic audio fidelity during mixing and overdubbing , so great effort was spent on getting the sound of the synthesiser right, before it reached the mixing desk.

While Vangelis had avoided using the big modular analogue synthesisers as performance instruments, some of their components were used for linking other machines. They were also used as a tool for generating sequencers, by driving other synthesisers. An example of this included the Roland System 717A, and Korg PS-3300. These machines demanded a long time to setup before something could be played. However, Vangelis sought out other solutions which helped him achieve similar results more quickly.

When Vangelis required a simpler sequencer the compact Roland System-100 was easy to set up. This analogue sequencer featured two columns of twelve potentiometers for adjusting pitch. Later this Roland sequencer and other analogue synthesisers would become part of a powerful performance setup using voltage-control technology. This way was found to increase their potential for performing live improvised music.

Recording equipment upgrade, 1978

In the first three years at Nemo Studios, a lot of energy and effort was spent on maintaining the recording equipment. Vangelis’ busy working schedule gave little opportunity to make drastic improvements, and he was increasingly being limited by the old and outdated recording equipment. However, by 1978, Vangelis had a chance to take time out from his busy projects, so he decided to upgrade the recording equipment and mixing desk.

The first problem to be tackled was the tape machine. The Scully tape machine had its limitations, particularly when it was interfaced with dbx noise reduction for multitrack tapes. The dbx required a flat frequency response, and this was a priority when choosing a new multitrack tape machine. Vangelis also needed a machine which could provide the much needed Sync Master mode. The Lyrec TR-532 tape machine was acquired after it was found to meet perfectly with the required specification. The Lyrec tape machine boasted eight additional tracks over the old Scully, giving it a total of 24 tracks. It also provided a host of new features, which included Vari-Speed , Track Solo, Spot Erase and the convenient Auto-Locate, which would memorise up to 16 positions on the tape, plus two working positions.

For this upgrade, a further 8-channel dbx-158 unit was purchased and put next to the existing 16-channel dbx unit. This meant that all of the 24 tracks from the new Lyrec TR-532 multitrack tape recorder were processed with dbx noise reduction. It was from this point on that all of the subsequent works at Nemo Studios were recorded on the Lyrec TR-532 tape machine, and the dbx Type-I noise reduction was almost always used.

In conjunction with the new multitrack tape recorder, two new master tape machines were acquired for putting the final mix-down recording onto quarter-inch tape, these were two Ampex ATR-100s. The second ATR-100 was useful for doing editing work. The two ATR-100 tape machines were equipped with Dolby A-Type noise reduction, as this offered better noise reduction on final stereo recordings, although, in principle, the ATR-100 was a far higher specification compared with the Scully, as it was able to load the tape to a higher level, and therefore could be used without Dolby A-Type noise reduction.

Next to this equipment upgrade, Vangelis also replaced the outdated API mixing desk with a 36-channel Quad/Eight Pacifica mixing desk. The Pacifica was an in-line mixer, as opposed to the split-mixer of the previous desk. This resulted in a more compact design with almost double the channel capacity. In addition to the 36 channels, the Quad/Eight Pacifica had four auxiliary channels, and these were used for sending or receiving echo. The new mixer also had a patch bay for configuring the route of the signal to and from the tape recorders and the outboard equipment.

The new recording upgrades Vangelis made at Nemo Studios in 1978 marked a turning point in the studio’s audio fidelity. They did more than just add to the depth and warmth of Vangelis’ sound. They also allowed him to explore new sonic landscapes, which had been technically challenging with the older recording equipment. The first album to take advantage of the new equipment was ‘China’, and its symphonic arrangements clearly benefited from the upgrade.

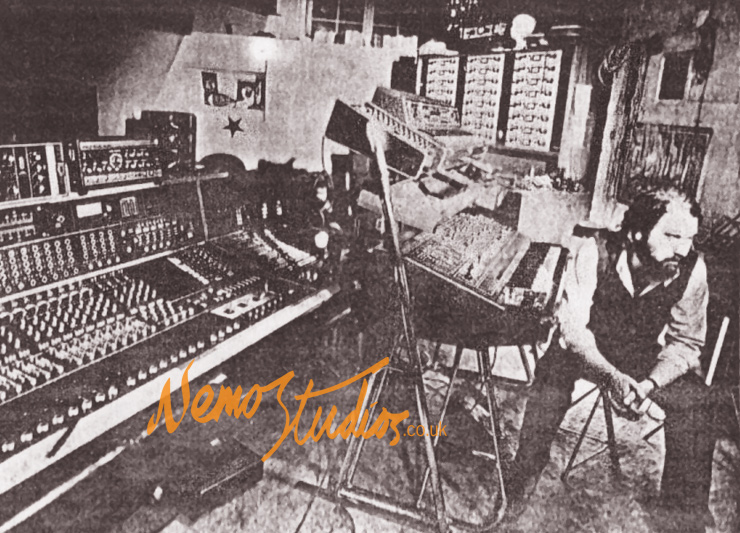

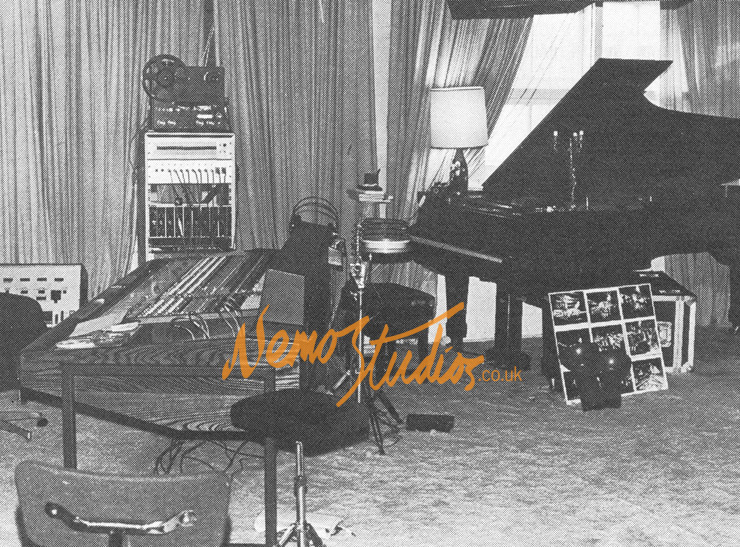

The new Quad/Eight Pacifica mixing desk just being installed at Nemo Studios. The Pacifica mixing desk was a US make manufactured by ‘Quad/Eight’, which was an unfamiliar name in the UK’s audio professional market. The Pacifica was used on all of Vangelis’ recordings starting with the album ‘China’.

Voltage-control

In the 1970s, analogue synthesisers used the principle of voltage-control as a means of communicating the desired pitch between synthesisers and other external devices, such as sequencers. The desired pitch was determined by generating a certain amount of voltage, which could be triggered by pressing a key on the keyboard or the voltage output of a sequencer’s control knob. At the time, analogue sequencers were quite primitive, and they only allowed monophonic sequences and patterns which, in most cases, were no longer than 16 notes. At that time, different manufactures used different schemes on how to map voltages to pitch values. Each manufacturer developed and promoted sequencers for their own synthesisers, although, in many cases, different machines were compatible.

As more synthesisers and sequencers were acquired and brought into Nemo Studios, several of them were linked together by using the principles of voltage control. A flexible voltage-control system was developed at Nemo Studios for live sequencer work, and it was extended to include drum machines, filters and more synthesisers, so that they could all run together and in sync . The system was intuitive to use, as it allowed Vangelis to focus his energy on the improvisational aspect, enabling him to transpose and edit the sequencers on the fly when performing his music, with all the connected synthesisers and sequencers keeping in time and following Vangelis’ musical direction. This system was a natural progression, going back to the way Vangelis had previously worked with his synthesisers and drum machines. It freed him from the constraints of lengthy programming and enabled him to produce a music scene which was instantly responsive and intuitively playable.

The voltage-control sequencer set-up was useful for improvisational work. However, this set-up was soon extended to allow a sequence to be rerun or a new sequencer line to be added on top of existing ones at a later convenient date. This was achieved after the development of a technique (at Nemo Studios) which enabled a ‘gate’ signal to be recorded onto tape, then, during playback, the trigger from the tape was used to let the sequencers and drum machines step in time. This meant that the final specification of the sequencers could - in theory - be modified or altered at a later date should this be necessary.

Triggering sequencers and drum machines from tape provided greater means for creating complex polyphonic sequencers and aural textures which were not possible with the hardware available at that point in time. Two examples of these were demonstrated on the sonic introduction on the composition ‘The Long March’, from the album ‘China’, and the repeating snare drum on ‘Chariots of Fire’, where the latter was the last overdub added to the track.

Nemo Studios’ equipment, synthesisers, and instruments, 1982

Analogue Synthesis

Yamaha CS-80 •

Roland VP-330 VocoderPlus MK I •

Sequential Circuits Prophet 10 •

Roland Jupiter 4 •

Yamaha CS-40M

Roland SH-09

Analogue Drum Machines

Roland CR-5000 CompuRythm •

Simmons SDSV with drum pad suitcase

CV/Gate Controllers and Sequencers

Roland ProMars CompuPhonic •

Roland CSQ-600 •

Roland CSQ-100

Roland System-100

Moog MiniMoog

RSF Kobol Black Box

ARP Sequencer

Digital Sampling Synthesis

E-Mu Emulator •

LINN LM-1 drum computer (preset)

FM Synthesis

Yamaha GS-1 •

Recording and Mixing

Quad/Eight Pacifica - 36 channel inline mixing desk •

dbx 216 16-channel Type I noise reduction - for multitrack tapes •

dbx 158 8-channel Type I noise reduction - for multitrack tapes •

Dolby A-Type noise reduction - for mixdown mastering •

Lyrec TR 532 2-inch 24-track tape recorder •

Ampex ATR-100 quarter-inch 2-track master tape recorder •

Studer 4-track master tape recorder (hired) •

Reverbs and Delays

Lexicon 224 digital reverb •

Master Room spring reverb

Compressors and Equalisers

Klark Teknik DN-27 graphic equaliser

Klark Teknik DN-22 graphic equaliser

URei 1176-LN peak limiter

Microphones

AKG-414, Sennheiser, and Electro-Voice

(different makes, all Mono)

Monitoring

Tannoy Dreadnought Monitors

BGW 750B amplifiers

• Indicates known or strongly suspected use on Blade Runner

Electro-Acoustical Keyboards

Fender Rhodes 88 suitcase piano •

Yamaha CP-80 piano •

Acoustic Keyboard

Steinway & Sons Concert Grand Piano •

Organ

Hammond B3

Acoustic Instruments

20-inch circular saw blade

Bell trees

Crotales

Gamelan

Glockenspiel

3 hand-tuned Timpani

Koto - Japanese stringed instrument •

Standard drum kit

Symphonic gongs

Symphonic snare drum

Thunder sheet

Tubular bell

Vibraphone

Wind gong

Recommended readings

Chariots’ One-Man Symphony, William Tuohy, Los Angeles Times, 3 April 1982.

Vangelis: Oscar-Winning Synthesist, Bob Doerschuk, Keyboard, August 1982.

Mechanic of Music, Andrew Duncan, Telegraph Sunday, November 1982.

Vangelis speaks, Dan Goldstein, Electronics & Music Maker, December 1984.

Vangelis: Career, Myth & Odyssey, Jean-Christophe Arion and Didier Leprêtre, Dreams, February/March 2002.

From the heart: The Power of Music, Michael Bond, New Scientist, 29 November 2003.

Future Noir, Paul M. Sammon, Orion Publishing, 2007.

Recommended viewings

On the Edge of Blade Runner, Mark Kermode, Channel 4, 2000.

Dangerous Days: Making Blade Runner, Charles de Lauzirika, Warner Home Video, 2007.

Blade Runner - The Final Cut, Ridley Scott, Warner Bros, 2007.

Other related web sections

PORTRAIT OF A RECORDING STUDIO - ARTICLE

PORTRAIT OF A RECORDING STUDIO - ARTICLE

A look at Vangelis’ Nemo Studios

SWEET NEMORIES - PHOTO SLIDESHOW

SWEET NEMORIES - PHOTO SLIDESHOW

Vangelis’ studio slideshow (endless loop)

A MUSICAL JOURNEY - ARTICLE

A MUSICAL JOURNEY - ARTICLE

Vangelis’ workography

MAIN WEBSITE

MAIN WEBSITE

Back to main site

Vangelis’ film score for Blade Runner

Copyright © 2019 nemostudios.co.uk